“Our son would not be with us today if it weren’t for St. Baldrick’s,” says Phineas’ dad, Carlos. Read on to see how research saved the little boy’s life.

VIDEO: Phineas’ Story

On a mountain bike ride with a friend, 9-year-old Phineas was sailing along when he decided to take a risk and pedal over a bridge not meant for bicycle traffic. He wiped out in a big way.

But without so much as a single tear, he picked himself up, dusted himself off, and got back on the bike.

Compared to what this boy had been through two years before, that was nothing.

The Doctor’s Visit

It was spring 2013 when Phineas had a cold and slight fever that just wasn’t going away. So, his mom, Tina, brought him to the doctor’s office.

Because their usual pediatrician was out, they saw a different doctor who didn’t know the family’s medical history. When the doctor lifted up Phineas’ shirt, Tina noticed a rash.

It looked startlingly familiar.

“Having seen this on my daughter’s skin many years before, I said to this doctor, ‘Do you think we could call this petechiae?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah.’ That’s when I told him, ‘Did you know we had a daughter die of AML?’”

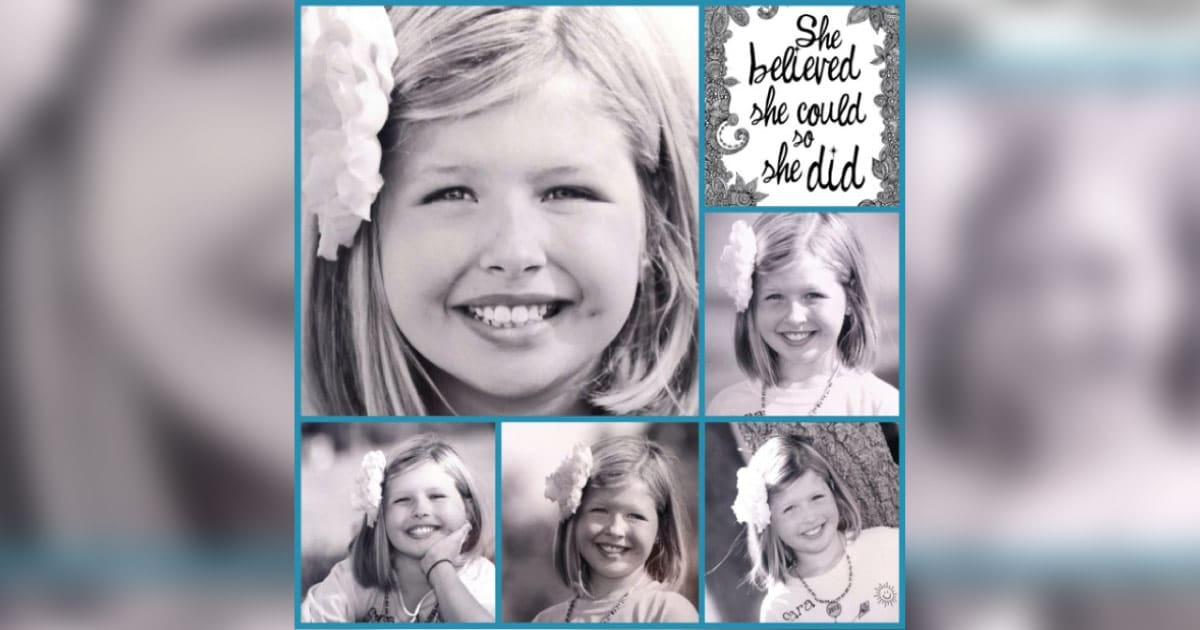

Phineas’ sister, Althea, smiles into the camera

Her name was Althea. The little girl with big brown eyes was 2 years old when she died from acute myeloid leukemia.

Fear Realized

That was two years before Phineas was born. The worry that Phineas would also get sick like his sister was always in the back on Tina’s mind.

“It was almost unreal that we were able to have another child and he was OK and healthy. It sort of seemed … fictional,” Tina said. “The whole thing was kind of a dream — like, did our daughter really get sick and die? Strange things happen to your mind when you lose a child.”

The doctor decided to run some tests. After drawing blood once from a crying and fearful Phineas, they wanted to do it again. His numbers were so out of whack that they thought the machine was broken.

“I’m starting to have a panic attack, because it’s really obvious to me that no, the machine’s not broken,” Tina said.

The Diagnosis

At 4 years old — six years after his sister’s death from childhood cancer — Phineas was diagnosed with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The doctor told Tina and Carlos to get Phineas to the hospital right away.

Phineas gets some play time in during a hospital stay.

Carlos said they were trying to stay positive in light of the news.

“But I think the most difficult part about that night was speaking with Fiona, our 11-year-old-daughter,” he said, recalling the conversation they had. “‘OK, well, this time it’s going to be different. You’re not going to lose another sibling — we don’t think.’”

Phineas started treatment immediately, but it was apparent early on that the chemotherapy wasn’t working like it does in most kids with ALL. It turned out that the ALL Phineas had was chemo-resistant, leaving him with very few options.

One of those long-shot options was getting Phineas on an immunotherapy clinical trial. So, his oncologist started making calls.

Time and time again, they struck out.

Finally, the family caught a break — what Carlos calls “the luckiest lucky break ever.”

The Immunotherapy Trial

That luckiest of lucky breaks was an immunotherapy trial headed by St. Baldrick’s Scholar Dr. Daniel Lee at the National Cancer Institute.

Phineas was accepted to the trial as patient number 10. Most of the other patients had gone through full treatment, went into remission and then relapsed, but Phineas was one of the first patients who was what they call primary refractory.

“Phineas was part of that 1%of the patients diagnosed in the United States who just don’t respond to their initial cycle or two of chemotherapy,” Dr. Lee explained. “For those patients, yes, you can try more chemotherapy and more intensive chemotherapy, but you really have a very, very, very low chance of curing a patient like that. For Phineas, there really was no other option.”

In a reversal of roles, Phineas uses a stethoscope to listen to Dr. Lee’s heart.

In this type of immunotherapy, called CAR T cell therapy, a patient’s own immune cells are modified — in Phineas’ case, T cells — and turned into the special CAR T cells, which identify and attack cancer cells.

T cells are part of your body’s natural defenses. They kill things that your immune system recognizes as a threat. Unfortunately, cancer has figured out how to fly under the immune system’s radar and evade T cells.

Dr. Lee and other immunotherapy researchers want to change that.

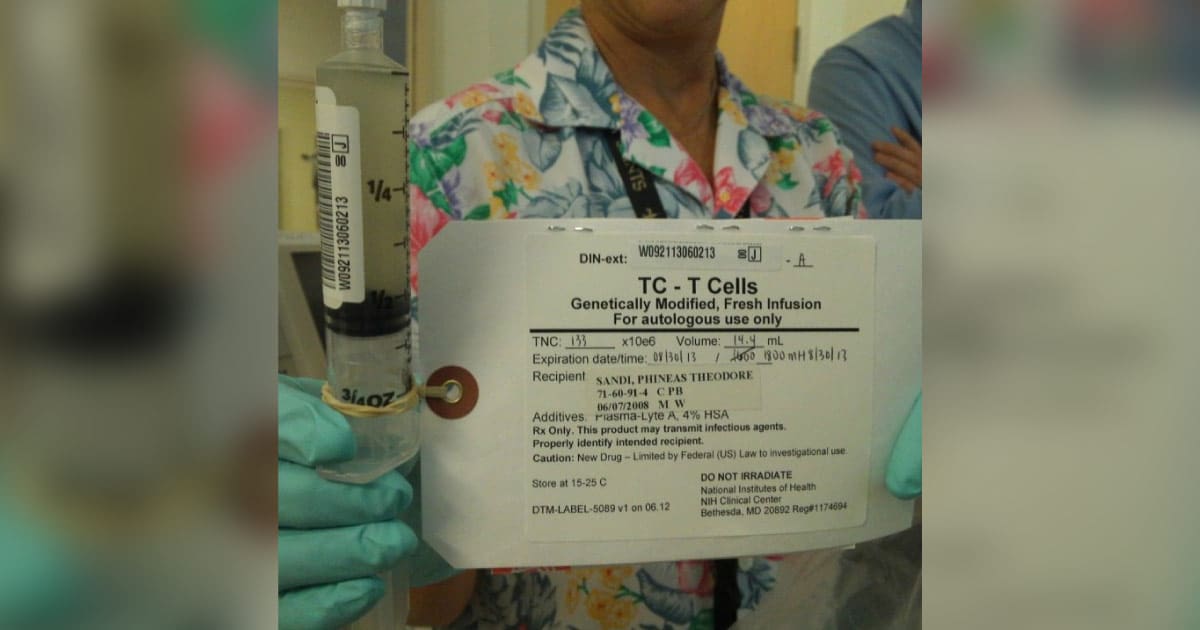

A nurse holds the single syringe of modified T cells used during Phineas’ immunotherapy.

During the trial, some of Phineas’ T cells were harvested through a blood draw, then grown and altered in the lab to lock onto cancer cells and destroy them.

Eleven days later, those CAR T cells were injected back into Phineas.

The cells then went to work.

For a few days, Phineas had a high fever and symptoms similar to a bad case of the flu. For a fleeting time he simply couldn’t talk, which was a reaction seen in some other patients.

Thankfully, the reaction, called cytokine release syndrome, is short-lived. More importantly, it’s actually a good indication that the treatment is working.

“Within a month after that Phineas was fortunately free of leukemia, as far as we could tell,” Dr. Lee said.

Phineas then went through a bone marrow transplant to give him a better chance to remain in remission.

Phineas and Dr. Lee share a well-deserved high five.

A Childhood Saved

Four years later, Phineas is still cancer free.

“Our son would not be with us today if it weren’t for St. Baldrick’s and their direct support of childhood cancer research,” Carlos said.

And there are other kids just like him who are waiting for us to unlock the answers to childhood cancer.

“We really can beat this. All these years of investment are just now starting to pay off huge,” he said. “We all need to get up off it and hit the accelerator and more kids will be saved.”

Phineas with his family. From left to right: His older sister, Fiona; his dad, Carlos; Phineas; and his mom, Tina.

Phineas will be starting third grade this year. He will be making new friends, learning new things and complaining about homework. After school, he plans to hang out with his friends, build robots and fight with his parents for more screen time.

He’s a regular kid. And he’s alive because of childhood cancer research funded by St. Baldrick’s.

The Sandi family is grateful for the kindness of strangers — all those people who shaved their heads for St. Baldrick’s, donated, organized events and volunteered.

“We’ve still got what’s left of our family because other people cared enough to help,” Carlos said.

Help more kids like Phineas get back to being kids. Give to childhood cancer research.